Указ №362 и Церковные Округа

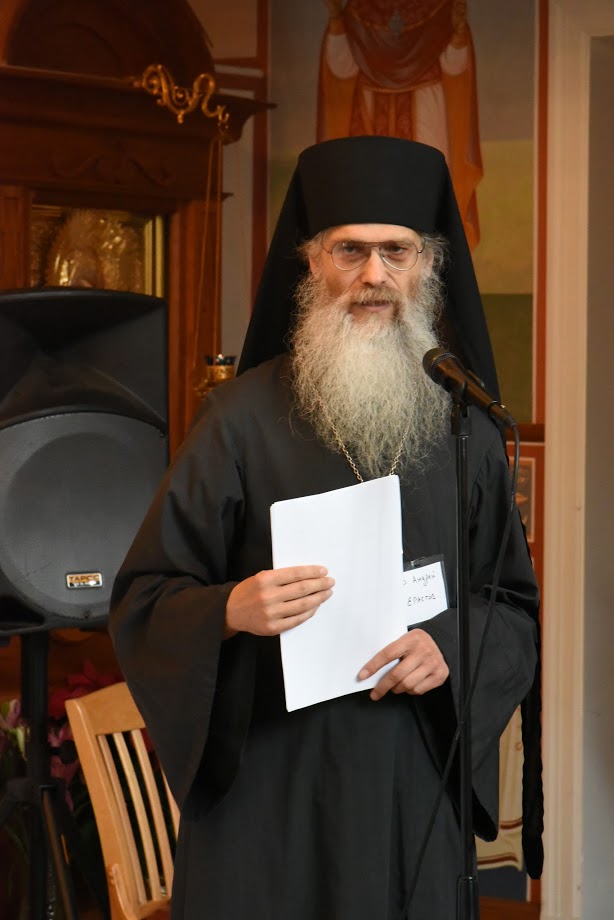

Игумен Андрей (Эрастов)

Январь 2017

Вступление

В 2007 г. корабль РПЦЗ потерпел крушение. Не многие спаслись от потопления на маленьких лодочках – «осколках» прежней Зарубежной Церкви.

Прошло почти 10 лет с того времени, и мы пришли к полному кризису. Ситуация настолько бедственная, что некоторые уже открыто говорят, что Зарубежной Церкви больше не существует и нужно подумать о переходе в другую юрисдикцию.

Какая причина такого критического положения? Наша главная проблема – это отсутствие ясного понимания: кто мы и каково наше церковно-каноническое положение. Мы живем в парадигмах прошлого, как-будто ничего не случилось, как-будто корабль не разбился, а попрежнему совершает благополучное плавание. Причем плывущие на каждой из лодочек претендуют на то, что именно их лодка является кораблем прошлого.

Как ни абсурдна такая точка зрения, но такова официальная экклезиология большинства «осколков». Отсутствие ясной канонической само-идентификации более всего разделяет нас и препятствует великому служению Церкви, ради которого стоит мир – свидетельству об истине.

Этой теме, т.е. выяснению нашего канонического положения, и посвящен это доклад.

Указ №362

Согласно Положению о РПЦЗ, «Русская Православная Церковь заграницей есть неразрывная часть поместной Российской Православной Церкви, временно самоуправляющаяся на соборных началах до упразднения в России безбожной власти, в соответствии с Постановлением Св. Патриарха, Св. Синода и Высшего Церковного Совета Российской Церкви от 7/20 ноября 1920 г. за № 362.». (1)

Т.е. каноническим основанием РПЦЗ является Постановление от 7/20 ноября 1920 года за № 362, обычно для краткости называемое Указом Патр. Тихона № 362. (2)

Указ №362 имеет огромное значение для всей Русской Церкви, и в особенности для РПЦЗ. Указ был издан от лица всех трех частей высшей церковной власти: патр. Тихона, Священного Синода и Высшего Церковного Совета.

На первый взгляд, Указ №362 имеет в виду лишь конкретную ситуацию, сложившуюся в годы Гражданской войны, когда многие епархии оказались отрезаны от Москвы линией фронта. Но в действительности значение Указа №362 гораздо шире. Это становится понятным, если мы проанализируем как текст самого Указа, так и обстоятельства, в которых он был издан.

К концу ноября 1920 г. Гражданская война уже почти закончилась победой большевиков. Становилось ясно, что Советская власть установилась надолго, на многие годы. Гонение на Церковь все усиливалось, большевики издавали один за другим анти-церковные декреты.

С другой стороны, подходил к концу срок полномочий Св. Синода и Высшего Церковного Совета. Согласно постановлению Поместного Собора 1917-1918 гг., Высшая Церковная власть в Русской Церкви разделялась на три ветви: Патриарх, Св. Синод и Высший Церковный Совет (последний занимался хозяйственными вопросами и включал в себя членов из духовенства и мирян). Члены Св. Синода и Высшего Церковного Совета избирались на трехлетний срок, до следующего Поместного Собора, который должен был созываться каждые три года. Однако, было очевидно, что Советы не допустят созыва нового Поместного Собора, и следовательно, будет невозможно избрать новый состав Св. Синода и ВЦС. Также в случае смерти Св. Патриарха будет невозможно избрание нового Патриарха.

Все эти обстоятельства оговариваются в Указе №362, а именно: «если Священный Синод и Высший Церковный Совет по каким-либо причинам прекратят свою деятельность», или все «Высшее Церковное управление во главе со Святейшим Патриархом прекратит свою деятельность».

Как и предвидели творцы Указа, Высшее Управление Русской Церкви вскорости прекратило свою деятельность: вначале временно, в 1922 г., во время обновленчества. А затем, в 1927 г. Советам удалось полностью подчинить себе Высшее Церковное Управление.

Таким образом, Указ №362 дает общие руководящие указания, как должна быть устроена каноническая, соборная жизнь русской Церкви, если высшая церковная власть по той или иной причине не сможет функционировать. Мы не признаем каноничность церковного руководства Московской Патриархии, следовательно, Указ №362 является основным каноническим актом Русской Церкви, на основании которого должна быть устроена наша церковная жизнь. Этот Указ никто не отменял и не может отменить, так как не существует инстанции, которая могла бы его отменить, т.е. Поместного Собора свободной Русской Церкви.

Собственно к РПЦЗ относятся 2-й и 3-й пункты Указа:

2) В случае, если епархия, вследствие передвижения фронта, изменения государственной границы и т. п. окажется вне всякого общения с Высшим Церковным Управлением или само Высшее Церковное Управление во главе со Святейшим Патриархом прекратит свою деятельность, епархиальный Архиерей немедленно входит в сношение с Архиереями соседних епархий на предмет организации высшей инстанции церковной власти для нескольких епархий, находящихся в одинаковых условиях (в виде ли Временного Высшего Церковного Правительства или митрополичьего округа, или еще иначе).

3) Попечение об организации Высшей Церковной Власти для целой группы оказавшихся в положении, указанном в п. 2 епархий, составляет непременный долг старейшего в означенной группе по сану Архиерея.

Таким образом, в случае, если несколько епархий теряют возможность общения с церковным центром, Указ предписывает образование из этих епархий временно-автономной структуры, например, митрополичьего округа.

Первейшая цель этого постановления – соборность. Это особенно видно из 5-го и 6-го пунктов Указа №362. В 5-м пункте говорится о ситуации, когда епархия оказалась отрезанной от центра, но у архиерея нет возможности установить контакт с епископами соседних епархий. Поскольку епархия может иметь только одного правящего епископа, то такая отрезанная от центра епархия лишается соборности. В таком случае, Указ рекомендует разделить эту епархию на несколько епархий, передать викариям права самостоятельных архиереев, т.е. создать архиерейский собор, и тогда разделенная таким образом «епархия образует из себя во главе с Архиереем главного епархиального города церковный округ, который и вступает в управление местными церковными делами, согласно канонам.» (пункт 6)

Митрополичий округ

Остановимся на этом понятии «церковный», или «митрополичий» округ. Митрополичий округ – это изначальная каноническая единица. Ко времени 1-го Вселенского Собора (325 г.) Церковь в Римской империи состояла из множества автокефальных митрополичьих округов (3). Такие малые автокефальные Церкви состояли из нескольких небольших епархий и обычно совпадали с границами римских провинций. Во главе стоял митрополит, т.е. епископ митрополии – главного города провинции (4). Митрополичьи округи были независимыми и автокефальными, т.е. собор епископов митрополии поставлял себе митрополита.

Каноническое устройство митрополичьего округа описывается в Ап. каноне 34: «Епископам всякого народа (здесь: области, провинции) подобает знать первого в них, и признавать его как главу, и ничего превышающего их власть не творить без его рассуждения: творить же каждому только то, что касается до его епархии, и до мест к ней принадлежащих. Но и первый епископ ничего да не совершает без рассуждения всех епископов. Ибо так будет единомыслие, и прославится Бог о Господе во Святом Духе, Отец, Сын и Святой Дух.».

Это Апостольское правило изображает соборный строй Церкви. Епархиальные архиереи не должны без согласия Первоиерарха делать что-либо, превышающего их обычную компетенцию. Но и Первоиерарх не самовластен: он должен обращаться к “рассуждению всех,” т. е. к решению Собора епископов его области.

Ко времени 1-го Вселенского Собора митрополичьих округов насчитывалось в Римской империи около сотни. (5) (Это число можно определить, исходя из числа провинций Империи. Если учесть, что во время 1-го Всел. Собора число всех епископов было около 1800, то в среднем получается 18 епископов на округ. (Википедия))

Для нашего церковного сознания привычно, что в каждой православной стране имеется одна автокефальная церковь. Снова отметим этот факт, непривычный для нас: в одном государстве, Римской Империи, в начале 4-го века соборная Церковь представляла собой семью небольших автокефальных Церквей, числом около ста. Эти автокефальные Церкви не были объединены на административном уровне, но в то же время сознание единства соборной Церкви в то время было гораздо сильнее, чем сейчас. В случае особой нужды созывались соборы епископов нескольких областей и, конечно, вселенские соборы.

Интересно отметить, что такое административно раздробленное устройство Церкви сложилось в эпоху язычества и гонений, а когда Империя стала христианской, административная структура Церкви стала укрупняться: начался процесс объединения автокефальных митрополий в патриархаты. Однако, это объединение создавалось не канонами, а самой жизнью. Каноны скорее тормозили этот процесс административного объединения. (6) Каноническое законодательство не только не упраздняло митрополичьих округов, а наоборот, требовало их дальнейшего существования. (7)

Поместный Собор 1917-1918 г.

Русская Церковь никогда не делилась на округа. От начала Русская Церковь была образована, как один митрополичий округ, во главе с митрополитом Киевским, (затем – Московским). Требование соборности, изображаемое 34 Апостольским правилом, русские епископы выполняли по отношению к Митрополиту, а затем к Патриарху Всероссийскому. (8)

После упразднения патриаршества императором Петром и замены его Святейшим Синодом (1721 г.) нарушился канонический порядок: вместо первого епископа во главу Церкви была поставлена безличная синодальная канцелярия, под руководством чиновника – обер-прокурора. По своему устройству Церковь стала представлять один из департаментов государства. Принцип соборности, выражаемой в соборе епископов, почти полностью отсутствовал в Русской Церкви в синодальный период.

Такое положение продолжалось до Поместного Собора 1917-1918 г., когда было восстановлено патриаршество. Однако деятели Поместного Собора опасались, что из-за большого числа епархий Русской Церкви (около 70) Патриарх не будет иметь возможности личного контакта с епископами, не будет иметь ясного представления о состоянии каждой епархии. Таким образом, соборность не будет реализована в церковной жизни, просто вместо синодальной канцелярии появится патриаршая канцелярия, которая будет завалена бумажными делами.

Нужно было образовать какое-то промежуточное звено между высшей церковной властью и епархиями. Таким звеном должны были стать митрополичьи округа. Как говорилось на Соборе: «Соборности епископов не будет без соборов митрополичьих округов. Никакого возрождения церковной жизни не произойдет в епархиях, обособленных одна от другой. Высшая церковная власть не в силах управлять одна, сосредотачивая все дела у себя в центре, надо предоставить решение большинства дел на местах.» (9)

Было решено образовать митрополичьи округа из незначительного числа епархий в каждом округе. При объединении епархий в округа принималось во внимание: церковно-бытовые условия, удобства путей сообщения, особенности административного деления местности, и проч. (10)

Священномуч. митр. Кирилл (Смирнов) был докладчиком на Соборе по теме митрополичьих округов. Он говорил в своем докладе: «Разнообразие интересов и бытовых особенностей жизни на огромных пространствах России требует, чтобы церковные округа не заключали в себе слишком много епархий. Мудрено, например, заключить в один округ хотя бы все Поволжье, так как особенности жизни и церковные нужды далеко не одни и те же у Казани, например, и Астрахани. Не одинаковы они и на обширном пространстве Сибири».

Окружной собор должен был иметь следующие функции: намечать вопросы, возникающие в епархиях округа и подлежащие обсуждению Поместного Собора; давать свои заключения Святейшему Патриарху по вопросу об открытии в округе новых самостоятельных епархий; участвовать в выборе епископов на вдовствующую кафедру и совершать хиротонию избранного и утвержденного Высшею Церковною Властью; рассматривать дела о прославлении святых к местному чествованию и проч.

Митрополит округа должен был: созывать окружные соборы и председательствовать на них; доводить до сведения Святейшего Патриарха о состоявшихся на соборе постановлениях и проч.

Одним из аргументов противников создания митрополичьих округов было то, что это нововведение может способствовать развитию сепаратизма. Против этого возражали, что к сепаратизму в большей степени приводит насильственная централизация, а не децентрализация.

Нужно подчеркнуть существенное различие между митрополичьими округами древней Церкви и митрополичьими округами, введенными Поместным Собором. Оно состояло в том, что последние не были автокефальными, а подчинялись общей высшей церковной власти.

В решении Поместного Собора, принятом 6(19) сент. 1918 г., говорилось: «Считая отсутствие церковных округов одним из старых недочетов Русской Церкви…и принимая во внимание количество епархий, возглавляемых Патриаршеством…Священный Собор, в целях осуществления полного канонического устройства Русской Церкви, учреждает церковные округа, а самое количество округов и распределение епархий по округам поручает Высшему Церковному Совету». (11)

Однако, политические обстоятельства не давали возможности провести в жизнь это решение Поместного Собора. Вследствие гражданской войны ВЦУ Русской Церкви не имело связи с более чем половиной епархий. В этой обстановке было бы бессмыслено определять границы церковных округов. Епархии, не имевшие связи с Москвой, стали сами создавать временные органы церковного управления. На таком историческом фоне был создан Указ №362. В нем отчасти зафиксирован тот опыт церковной жизни, который сложился стихийно на территориях, оторванных от центра гражданской войной. Вообще, это типично, что церковные правила утверждают уже сложившуюся практику. По большей части так это и было в древности.

Мы достаточно подробно остановились на решениях Поместного Собора о митрополичьих округах, так как вне этих решений невозможно правильно понять Указ №362.

Указ №362 и Зарубежная Церковь

Основой будущей РПЦЗ было Временное Высшее Церковное Управление юго-востока России (ВВЦУ), созданное в 1919 г. на территориях, занимаемых армиями ген. Деникина. После эвакуации из Крыма в 1920 г. оно продолжило свою деятельность под именем ВРЦУ (Высшее Русское Церковное Управление). 6/19 ноября 1920 г. на пароходе “Великий Князь Александр Михайлович” в Босфорском проливе состоялось первое (за границей) заседание ВРЦУ. В заседании приняли участие: митроп. Антоний (Храповицкий), митрополит Платон (Рождественский), архиепископ Феофан (Быстров) и др.

Образование зарубежного высшего церковного управления настолько соответствовало церковному восприятию того времени, что почти все зарубежные архиереи (их было более 30) признали ВРЦУ (с 1922 г. переименованое во Временный Заграничный Архиерейский Синод). (12) Так было в начале, но впоследствии стали действовать центробежные силы, и произошли расколы (в 1926 г.)

Указ №362 был издан 7/20-го ноября 1920 г., (т.е. днем позже 1-го заграничного заседания ВРЦУ), но стал известен за рубежом только в начале 1922 г. Таким образом, основы канонического устройства РПЦЗ были заложены раньше, чем Указ №362 стал известен иерархам РПЦЗ. Этим, отчасти, объясняется тот факт, что ее устройство не вполне соответствует букве этого Указа. РПЦЗ основана на Указе №362 в том отношении, что в условиях отрыва от центральной церковной власти зарубежные архиереи создали высшее церковное управление. Однако, устройство этого управления не полностью совпадало с Указом №362.

Действительно, Указ №362, предвидя возможность отрыва нескольких епархий от центральной высшей церковной власти или даже возможность прекращения ее деятельности, предписывает епархиям, находящимся в одинаковых условиях, организоваться на соборных началах, как митрополичий округ, но ничего не говорит о возможности создания какого-либо общего высшего церковного управления над несколькими такими округами. Т.е. Указ не предвидит создания общего церковного центра для всего зарубежья, подобного тому, который был образован в Сремских Карловцах.

Мысль устроителей РПЦЗ хорошо прослеживается по резолюции 1-го Всезаграничного Собора (ноябрь 1921 г.) «о Высшем Русском Церковном Управлении за границей». (Напомним, что Указ №362 за границей тогда еще не был известен). Согласно этой резолюции, ВРЦУ являлось точным подобием Высшего Церковного Управления в России. Оно должно было быть возглавлено патриаршим Наместником и состояло из Русского Заграничного Синода и Церковного Совета. (38) Однако, Патриарх Тихон не одобрил мысль о назначении патриаршего Наместника за границей. Таким образом, по мысли его устроителей, ВРЦУ было не возглавлением одного митрополичьего округа, а как и следует из его названия, высшей церковной властью для заграничной части Русской Церкви, свободной от большевиков.

Карловацкий Синод упрекали в том, что он претендует на роль всероссийского Св.Синода, не имея на то никаких полномочий высшей церковной власти. (13) С формальной стороны, эти упреки справедливы, но нужно учитывать тот факт, что Высшее Церковное Управление в России при патр. Тихоне было несвободно, а при митр. Сергии и вовсе стало инструментом влияния большевиков. Напротив, Синод РПЦЗ видел себя как церковное управление свободной части Русской Церкви.

Отсюда в среде зарубежного епископата возникала мысль о том, что зарубежный Синод, возглавляемый митр. Антонием, может говорить от лица всей Русской Церкви и даже, в случае прекращения деятельности ВЦУ в России, может возглавить не только зарубежную часть Церкви, но и всю Русскую Церковь из-за рубежа. Например, после смерти св. патр. Тихона Синод постановил 9 апреля 1925 года: «Предоставить Председателю Архиерейского Синода Высокопреосвященному Митрополиту Антонию, с правами временного, до созыва канонического Всероссийского Священного Собора, заместителя Патриарха, представительствовать Всероссийскую Православную Церковь и, насколько позволяют условия и обстоятельства, руководить церковной жизнью и Церковью не только вне России, но и в России». (14)

Такое воззрение на РПЦЗ, как на свободный голос Русской Церкви, существовало до последнего времени, до времени ее соединения с МП.

Противники Карловацкого Синода: Митр. Евлогий, проф. С. Троицкий и др. утверждали, что деятельность митр. Антония и его сподвижников по укреплению центральной церковной власти за рубежом была не нужна и даже вредна для Церкви. Конечно, это совершенно ошибочный взгляд. Существование Синода было оправдано его высоким духовным авторитетом и авторитетом его первоиерарха. Так выразил это сербский патр. Варнава, проповедуя в русской Свято-Троицкой церкви Белграда: «Среди вас находится митрополит Антоний, этот великий иерарх, являющийся украшением Вселенской Православной Церкви. Это высокий ум, который подобен первым иерархам Церкви Христовой в начале христианства. В нем и заключается церковная правда. Вы все, не только живущие в нашей Югославии, но и находящиеся в Европе, в Америке и в Азии и во всех странах мiра должны составлять, во главе с вашим великим архипастырем, митрополитом Антонием, несокрушимое целое, не поддающееся нападкам и провокациям врагов Церкви». (15)

Синод РПЦЗ в течение десятилетий являлся носителем церковной правды не только для Русской Церкви, но и для всей вселенской Церкви. Однако, с формальной стороны, Зар.Синод не имел санкций от Высшей Церковной власти Русской Церкви. Напротив, ВРЦУ даже было упразднено Указом №348 патр. Тихона от 5 мая 1922 г. В том же году собравшийся в Сремских Карловцах собор архиереев формально исполнил волю патриарха Тихона, распустив Высшее Русское Церковное Управление, но, предполагая, что указ Первосвятителя был дан под давлением Советской власти, учредил вместо ВРЦУ Временный Заграничный Архиерейский Синод, который так же не был утвержден Патриархом.

Несомненно, Указ №348 был издан под давлением большевиков, но в таком случае св. патр. Тихон, издавая этот Указ, рассчитывал на то, что и произошло: т.е. что заграничные архиереи не подчинятся этому указу. По большей части, церковная жизнь устрояется не по букве указов и канонов, напротив, каноны утверждают и санкционируют церковный строй, который устанавливается самой жизнью. В противном случае, указы остаются лишь на бумаге и не имеют влияния на жизнь Церкви.

Единый церковный центр зарубежья был образован отнюдь не в результате беспочвенных претензий и властолюбия каких-либо отдельных лиц, как утверждали его критики, а был произведен самой жизнью и поддерживался церковным сознанием иерархии, а не буквой указов. Широко известно высказывание церковного историка проф. В. Болотова: «Каноничным следует считать то, что полезно для Церкви». (16)

Но Указ №362 не санкционирует единый церковный центр зарубежья, и нет никаких других канонических актов, которые бы санкционировали его существование.

Большинство зарубежных архиереев добровольно подчинились ВРЦУ, так как для церковного сознания было непонятно, как можно обходится без единого церковного центра. Митрополичьи округа были недавним нововведением Поместного Собора Русской Церкви, на практике еще не реализованным, и, вероятно, мало кому известным.

Чтобы показать, насколько идея митрополичьих округов в духе Поместного Собора и Указа №362 была еще мало усвоена российским епископатом, достаточно указать на следующий пример. В 1923 г. в Сремских Карловцах состоялся очередной Архиерейский собор. Немогущим прибыть на собор епископам был послан ряд вопросов, главный из которых был: «Признаете ли Вы необходимость существования высшего церковного института для управления заграничными епархиями или считаете возможным, чтобы иерархи управляли своими епархиями автономно». (17) Этот вопрос предполагает только два варианта: существование единой высшей церковной власти или полностью раздробленное существование каждой епархии в отдельности. Возможность объединения нескольких епархий в церковные округа даже не рассматривается. Вообще, в споре сторонников единого заграничного церковного центра и его противников заметно, что первые не вполне понимают принцип митрополичьих округов. В этом смысле интересна полемика проф. С. Троицкого и Г. Граббе.

Спор С. Троицкого и Г. Граббе.

Проф. С. Троицкий, крупнейший в зарубежье специалист в области канонического права, издал в 1932 г. книгу «Размежевание или Раскол», в которой обвинял Синод в Сремских Карловцах в незаконных притязаниях на управление всей русской диаспорой. Он считал эти претензии главной причиной разделений в РПЦЗ, происшедших в середине 20-х годов. Ему в том же году ответил Г. Граббе, будущий еп. Григорий, секретарь Синода, в статье «Единение или Раздробление». Интересно рассмотреть этот поединок таких весьма сильных противников.

С. Троицкий, участник Поместного Собора, (он был делопроизводителем канцелярии Поместного Собора, его подпись стоит под Докладом о Церковных Округах св. Кирилла(18)), доказывал, что «Точным выполнением Указа №362 была бы организация за границей нескольких временно автономных митрополичьих округов, возглавляемых и управляемых своими соборами епархиальных епископов под председательством окружных митрополитов.» (18)

Таких округов, по его мнению, должно было быть четыре: Западно-Европейский, Ближне-Восточный (имеется в виду восточная Европа), Северо-Американский и Дальне-Восточный.

«Такое размежевание (т.е. на четыре округа) вовсе не исключает возможности образования общих Соборов епископов этих округов, но лишь для решения вопросов чрезвычайной важности и, во всяком случае, никакого постоянного органа высшего Церковного Управления в виде Синода, Высшего Церковного Совета и т.д. создавать не нужно.» (19)

«Вся заграничная часть Русской Церкви, разделенная на несколько автономных митрополичьих округов, объединенных периодически созываемым общим Собором, пребывала бы в мире и спокойствии». (20) «Стремление сохранить непрерывное единство церковного управления, своего рода церковный империализм, и является главной причиной церковных нестроений» (21)

Указ №362 предписывает в случае, если епархия окажется отрезанной от центра, чтобы епархиальный Архиерей вошел в сношение с Архиереями соседних епархий на предмет организации высшей инстанции церковной власти для нескольких епархий, находящихся в одинаковых условиях.

По мнению проф. Троицкого, все зарубежье не могло быть организовано как один митрополичий округ, потому что все епархии русской диаспоры не могли рассматриваться как «находящиеся в одинаковых условиях». Он возражал: «В самом деле, разве можно назвать соседними и находящимися в одинаковых условиях русские епархии в Югославии, в Китае и Америке?» (22) Трудно считать находящимися в одинаковых условиях епархии, находящиеся на огромном расстоянии друг от друга. Одинаковым было лишь их свободное положение по отношению к большевицкой России.

Положение русских людей, живших в различных государствах, в различных политических системах, в различных частях света, очень различалось. А как мы помним, при обсуждении на Поместном Соборе вопроса распределения епархий Русской Церкви по митрополичьим округам, прежде всего принимались во внимание общие нужды населения и легкость сообщения между епархиями. Например, в докладе св. митр. Кирилла на Поместном Соборе дается приблизительное разделение епархий Русской Церкви на митрополичьи округа. Согласно этому разделению, Северо-Американские епархии составляют один церковный округ, который, конечно, не включает в себя все зарубежные епархии. (23)

Г. Граббе возражал ему: «Если все епископы согласны и желают объединиться, то почему же им этого не сделать? Если имеет право на образование высшего Церковного Управления или Митрополичьего округа каждая отдельная оторванная епархия, то по какой логике г. Троицкий оспаривает то же право у их совокупности? Моральный же вес объединенной Русской Церкви во всяком случае всегда будет больше, чем вес ее в раздробленном виде.» (24) «Странно говорить и о невозможности иметь один центр для всей заграничной Церкви после того, что уже больше 10-ти лет существует такой центр.» (25) «ВРЦУ объединило все зарубежные епархии… Это объединение еще не обосновалось на Постановлении 1920 г. (Указ №362) потому, что его еще не знали, но здоровое церковное сознание всем подсказывало, что заграничная Церковь должна быть объединена, что, объединенная, она имеет значительный вес, который может послужить на пользу и гонимым братьям в России». (26) «Благо Церкви отнюдь не требует дробления, а кроме того оно не может пройти безболезненно, раз находит его невозможным и ненужным подавляющее большинство русских архиереев». (27)

Г. Граббе убедительно аргументирует в пользу объединения всей заграничной части Русской Церкви. Существование Синода обосновывается им на соображениях церковной пользы и на том, что он произведен самой жизнью и принят церковным сознанием большинства архиереев. Однако, Г. Граббе не имеет сильных аргументов против утверждения С. Троицкого, что единый церковный центр зарубежья не соответствует как букве, так и мысли Указа №362. Если и можно, с некоторой натяжкой, оправдать такой центр на основании Указа №362, то справедливо и обратное: т.е. если бы в Зарубежье было изначально организовано несколько церковных округов, то на основании Указа №362 было бы невозможно требовать подчинения их одному центру.

Сам митр. Антоний рассматривал РПЦЗ как единый митрополичий округ. Он пишет митрополиту Елевферию Литовскому (1934 г.): «За границей, на основании указа от 7/20 ноября 1920 года давно уже образована временная митрополичья область, во главе коей я и нахожусь.» (28)

Если РПЦЗ было объединением епархий в один митрополичий округ, то как тогда объяснить тот факт, что внутри РПЦЗ были части, выделенные в меньшие митрополичьи округи? Так, по определению архиерейского собора 1923 г., Западно-Европейская епархия была выделена в автономный митрополичий округ.

В 1935 г. на Архиерейском Соборе была произведена попытка преодолеть церковные разделения путем создания митрополичьих округов. Согласно Временному Положению о Русской Православной Церкви за границей (1936 г.), были образованы четыре митрополичьих округа, состоящие из нескольких епархий. Округи выбирали своего митрополита и представляли кандидатуры для посвящения в епископы, которые утверждались Синодом. Так что округи были только частично автономны, и подчинялись Карловацкому Синоду. Таким образом, это Временное Положение было как бы компромиссным вариантом, сохраняющим и централизацию, и частичную автономию областей. Одними из творцов этого Положения были проф. С. Троицкий и Г. Граббе (29)

Временное Положение 1936 г. очень близко повторяет канонические формы митрополичьих округов, выработанные на Поместном Соборе 1918г. Только по Положению 1936 г., митрополичьи округа подчиняются зарубежному Синоду, тогда как митрополичьи округа, принятые Поместным Собором, подчинялись Высшей Российской церковной власти.

Отсюда совершенно очевидно, что Синод РПЦЗ не был возглавлением одного митрополичьего округа, в соответствии с Указом №362, а как бы альтернативой общецерковного высшего управления. Однако Указ №362 ничего не говорит о создании церковного центра, которому бы подчинялись несколько церковных округов. Такого образования Указ не предвидит и не предписывает. Отсутствие высшей церковной власти отнюдь не означает, что кто-либо может претендовать на такую власть, не имея на это санкций высшей церковной власти.

Значение Синода РПЦЗ для Русской Церкви можно видеть из того, что он очень мешал Советам. Они делали все, что было в их силах, чтобы уничтожить единый зарубежный церковный центр. Они действовали вначале через патр. Тихона, а затем через митр. Сергия, вынуждая их издавать указы об упразднении Карловацкого Синода. Причина этого очевидна. Синод митр. Антония придерживался монархической идеологии и стоял на непримиримой позиции по отношению к большевицкой власти, тогда как церковные центры в Америке и в Париже были гораздо либеральнее. Не имея возможности как-либо влиять на Карловацкий синод, большевики делали все возможное, чтобы ограничить его влияние на русское рассеяние.

Напротив, в Советской России большевики отнюдь не желали прекращения деятельности высшей церковной власти. Они боялись децентрализации, в соответствии с Указом №362, потому что в этом случае им было бы гораздо сложнее осуществлять свое влияние на всю Церковь. Они ставили целью подчинить церковную верхушку своему влиянию, чтобы через нее подчинить себе всю Церковь. (37)

Советские агенты десятилетиями трудились над духовным подчинением русской диаспоры. Их огромной победой было то, что Архиерейский Синод, единый церковный центр Зарубежья, сам стал подвержен пропаганде за соединение РПЦЗ с МП. Но представим себе, что РПЦЗ была бы организована, как несколько независимых округов, в таком случае это значительно усложнило бы задачу для деятелей соединения с МП. Если бы какой-нибудь из церковных центров поддался на московскую пропаганду, то другой, более консервативный центр, мог бы объединить здоровые силы, и мы не оказались бы в таком катастрофическом положении, в котором сейчас находимся.

Наше положение

Совершенно очевидно, что сейчас нельзя даже представить себе единый административный центр Русской Церкви, с другой стороны, его существование, возможно, и не было бы полезно. Церковная жизнь, как в России, так и за рубежом должна строиться на основании указа №362 – основного руководящего канонического документа. В соответствии с этим указом, должны быть сформированы на добровольных началах церковные округа, состоящие из нескольких епархий (не менее трех – четырех), (Автокефальной может быть лишь та Церковь, которая сама может поставлять и судить своих епископов. Для избрания нового епископа необходимо участие на соборе 3-х епархиальных епископов и утверждение 4-го – митрополита. (4-е правило 1-го Всел Соб.)) (30) Эти округа будут временно автономными, до восстановления законной канонической Высшей Церковной Власти в Русской Церкви.

Архиереи округа должны будут избрать из своей среды первоиерарха, в отношении к которому будут исполнять обязанности, налагаемые 34-м Апостольским правилом. Такие округа будут поддерживать между собой евхаристическое общение и тесные связи, выражающиеся в братском общении и взаимопомощи. По временам будут собираться общие соборы для разрешения общецерковных вопросов. Однако, в административном отношении каждый округ будет независимым. Нетрудно видеть, что такая организация Церкви будет возвратом к первохристианским каноническим формам.

У нас уже исторически сложились церковные образования, на подобие церковных округов – это так называемые «осколки». Конечно, эти церковные образования имеют большие недостатки, например, то, что они территориально накладываются друг на друга. Но у них есть и одно важное достоинство – они уже существуют. А церковное строительство имеет в виду наличный строительный материал. Собственно, проблема «осколков» не в самом дроблении, – это дробление имеет свои позитивные стороны, и оно вполне канонично. Так выглядела Церковь в древности, и подобное дробление предвидится Указом №362. Главная проблема «осколков» в том, что между ними нет литургического общения, и многие из них не имеют соборности.

В основание литургического общения между «осколками», как и было в древней Церкви, должны быть положены: православное исповедание и законность иерархии. Евхаристическое общение невозможно только с неправославными, неимеющими правильного рукоположения, или запрещенными клириками. Если этих препятствий не имеется, то нет никакой причины отказываться от совместного служения. Необходимо нам всем осознать ненормальность положения, когда православные архиереи не имеют евхаристического общения друг с другом и нисколько не заботятся об этом.

Таким образом, до восстановления законной высшей церковной власти Русская Поместная Церковь должна представлять из себя церковные округа, находящиеся в литургическом общении друг с другом. Процесс объединения «осколков» нужно видеть не в административном слиянии их в одну структуру или подчинении всех одному центру, а в том, чтобы между ними установилось евхаристическое и братское общение, вместо нынешнего соперничества, претензий и взаимных отлучений.

Принцип, выраженный в Положении о РПЦЗ: «Русская Православная Церковь заграницей есть неразрывная часть поместной Российской Православной Церкви, временно самоуправляющаяся на соборных началах.» – остается в силе. Однако, его нужно относить не к какой-либо одной части Зарубежной Церкви, а ко всем в совокупности.

«Осколки» оспаривают друг у друга каноническое правопреемство от дораскольной Зарубежной Церкви, однако, его не существует. Как было сказано выше, Синод РПЦЗ существовал не на основании каких-либо канонических актов, а скорее, вопреки им. Смысл существования Синода был в том, что он являлся носителем церковной правды. Когда же впоследствии Синод впал в соблазн сергианства, то он утерял всякое значение. Каноническое обоснование Синода было в его высоком духовно-нравственном авторитете и в соображениях церковной пользы. (Каноничным следует считать то, что полезно для Церкви. (В.В. Болотов)) (31)

Получается странная картина:«осколки» соревнуются за обладание несуществующим наследством. Наследство Зарубежной Церкви состоит не в каких-то особых канонических правах – их нет, а в духе истинной церковности, в мудрости царского пути, соединяющего твердое стояние в истине и хранение предания Церкви, но без уклонения в крайности фанатизма и сектантского мышления. К сожалению, о стяжании этого духовного наследства Зарубежной Церкви наши «осколки» нисколько не заботятся.

В высшей степени странно, когда какой-нибудь маленький «осколок», не имея за собой ни малейшего морального авторитета, претендует на высшую власть над всей Русской Церковью, на основании какого-то невнятного правопреемства от прежней РПЦЗ, как, например, это было сказано в недавнем «Заявлении Архиерейского Собора РПЦЗ». (32)

«Осколкам» нечего делить и не из-за чего соперничать. Все они являются временно-самоуправляющимися частями Русской Поместной Церкви, независимо от того, где они находятся, в России или за рубежом, и какой бы аббревиатурой они себя ни называли. Однако, им нужно организоваться на началах соборности, согласно с Указом №362, чтобы из «осколков» стать каноничными Церковными Округами.

Запрещения

Отдельно рассмотрим вопрос запрещений в священнослужении, которым подверглись некоторые «осколки». Иерархия большинства «осколков» имеет несомненное апостольское преемство, но каноничность их остается под вопросом, из-за того, что эти «осколки» при своем образовании были расценены как раскол и их епископат был подвержен запрещению.

Запрещения в священнослужении могут быть наложены с различной целью и имеют различный смысл. Например, запрещение может быть наложено на время, как наказание за какой-либо проступок, также запрещение налагается на обвиненного клирика прежде церковного суда над ним. В нашем случае бессрочное запрещение было наложено на епископов, вышедших из повиновения церковной власти и составивших свою отдельную юрисдикцию. Такое запрещение налагается на непослушных, чтобы вернуть их к послушанию. В истории Церкви такое случалось множество раз. Почти каждый раз, когда происходило отделение «дочерней» Церкви от Церкви-матери, это было связано с расколом и прещениями. Так это было, например, когда Болгарская Церковь самовольно отделилась от Константинополя в 1872 г.

Существуют только три возможности, чтобы такое запрещение было снято, и восстановился мир в Церкви. 1. Если непокорная группа епископов раскается и вернется в послушание церковной власти. 2. Если сама церковная власть смягчится и снимет запрещение. 3. При неуступчивости церковной власти запрещенные могут апеллировать к суду высшей церковной инстанции. (33)

Например, в 1935 г. произошло примирение между Синодом Зарубежной Церкви и митр. Евлогием и митр. Феофилом, которые вернулись в послушание Синоду, и с них были сняты запрещения.

Но в отношении «осколков», запрещенных Синодом РПЦЗ, (как например, Суздальская группа), проблема состоит в том, что больше не существует церковной власти, наложившей это запрещение (т.е. она впала в сергианство), и таким образом, нет возможности примириться и освободиться от запрещения. А запрещение может быть снято только той Церковью, которая его наложила, (Ап.правило 32; 1-го Всел. Соб. 5-е правило) или церковным собором, значительно более авторитетным. Также нет возможности и апеллировать к высшей церковной инстанции, поскольку ее для нас также не существует. Конечно, многие «осколки» претендуют на правопреемство от Синода РПЦЗ, но как уже было сказано, такие претензии беспочвенны.

Поскольку не имеется возможности по канонам снять прещения, наложенные Синодом РПЦЗ до 2007 г. или Синодом митр. Виталия (2001 г.-2007 г.), то уже не имеет смысла признавать эти прещения. Их нужно считать, как небывшие. Эти прещения могли бы быть сняты общим собором архиереев «осколков».

Что же касается взаимных запрещений, наложенных уже иерархией «осколков» друг на друга, то эти запрещения были подчас наложены на основании неверных канонических представлений. По этой причине их можно было бы просто игнорировать.

По слову одного современного церковного деятеля, «процесс “собирания осколков” должен на первой стадии быть больше “идейным”, а не организационно-административным. Пора, наконец, сформулировать яркую и убедительную идеологию, или, выражаясь богословским языком, “экклезиологию осколков”, которая постепенно станет более популярной и влиятельной, чем старая “административно-синодальная экклезиология”» (34)

По моему мнению, такая «экклезиология осколков» достаточно ясно определена Указом №362. Как это выразил прот. Николай Артемов: «По сути, Указом № 362 дана санкция на переустройство всей Русской Церкви по принципу митрополичьих или церковных округов, сохраняющих между собою духовное единение до возможности свободно определить свою общую жизнь на уровне всецелой Русской Церкви.» (35)

В заключение приведу слова одного из исповедников Русской Церкви: «Из истории мы видим, что частей Церкви Вселенской ничто подчас не объединяло, кроме причащения от Единого Хлеба-Христа, одного возглавления на небесах… Церковь не гибнет, когда внешнее ея единство разрушается. Она не дорожит внешней организацией, заботясь о сохранении своей истины. (36)

Примечания

1. Положение О Русской Православной Церкви Заграницей.

2. Постановление Святейшего Патриарха, Священного Синода и Высшего Церковного Совета Православной Российской Церкви от 7/20 ноября 1920 года за № 362.

3. Протоиерей Николай Артемов. К Всезарубежному Собору 2006 года.

4. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 12

5. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 12

6. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 13

7. Деяния Священного Собора Православной Российской Церкви 1917-1918 гг. Том 11-й. Деяние 168. стр. 197

8. Архивные Документы Священномученика Кирилла (Смирнова). Доклад Отдела о Высшем Церковном Управлении о Церковных Округах на Священном соборе 1917-1918 гг. стр. 257

9. Деяния Священного Собора Православной Российской Церкви 1917-1918 гг. Том 11-й. Деяние 168. стр. 200-201

10. Архивные Документы Священномученика Кирилла (Смирнова). Доклад Отдела о Высшем Церковном Управлении о Церковных Округах на Священном соборе 1917-1918 гг. стр. 259

11. Деяния Священного Собора Православной Российской Церкви 1917-1918 гг. Том 11-й. Деяние 169. стр. 216

12. Протоиерей Николай Артемов. Постановление № 362 от 7/20 ноября 1920 г. и закрытие зарубежного ВВЦУ в мае 1922 г.

13. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 142

14. Архиеп. Никон, Жизнеописание митр. Антония. т. 6, стр. 205-206. цит. по В. Русак. Русская Зарубежная Церковь.

15. М.В. Шкаровский. Возникновение Русской Православной Церкви Заграницей и Религиозная Жизнь Российских Эмигрантов в Югославии. стр. 151

16. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 33

17. М.В. Шкаровский. Возникновение Русской Православной Церкви Заграницей и Религиозная Жизнь Российских Эмигрантов в Югославии. стр. 110

18. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 134

19. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 137

20. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 45

21. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 7

22. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 49

23. Архивные Документы Священномученика Кирилла (Смирнова). Доклад Отдела о Высшем Церковном Управлении о Церковных Округах на Священном соборе 1917-1918 гг. стр. 261

24. Еп. Григорий (Граббе). Церковь и Ее Учение в Жизни. том 1-й. Монреаль 1964. стр. 209

25. Еп. Григорий (Граббе). Церковь и Ее Учение в Жизни. том 1-й. Монреаль 1964. стр. 210

26. Еп. Григорий (Граббе). Церковь и Ее Учение в Жизни. том 1-й. Монреаль 1964. стр. 215

27. Еп. Григорий (Граббе). Церковь и Ее Учение в Жизни. том 1-й. Монреаль 1964. стр. 219

28. Архиеп. Никон, т. 7, стр. 355-357. Цит. по Владимир Русак. Зарубежная Церковь и митрополит Сергий.

29. Протопресвитер Георгий Граббе. Правда о Русской Церкви на Родине и за Рубежом. Jordanville, N.Y., 1961, стр. 3—5.

30. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 36

31. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 33

32. http://internetsobor.org/index.php/novosti/rptsz/rptsz-zayavlenie-arkhierejskogo-sobora

33. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. стр. 65-66

34. А. Солдатов. Главный редактор вебсайта «Портал-Кредо»

35. Протоиерей Николай Артемов. К Всезарубежному Собору 2006 года.

36. Протоиерей Михаил Польский. Каноническое положение высшей церковной власти в СССР и заграницей .

37. Из письма Троцкого в Политбюро: «Централизованная церковь при лойяльном и фактически бессильном патриархе имеет известные преимущества. Полная децентрализация может сопровождаться более глубоким внедрением церкви в массы путем приспособления к местным условиям.» Лекция прот. Г. Митрофанов. «История Церкви ХХ века сквозь призму личности Патриарха Тихона»

38. ДЕЯНИЯ РУССКОГО ВСЕЗАГРАНИЧНОГО ЦЕРКОВНОГО СОБОРА 21 ноября – 3 декабря 1921 года в Сремских Карловцах.

Источники и литература

1. Епископ Григорий (Граббе). Каноны Православной Церкви. http://lib.pravmir.ru/library/readbook/2286#sel=

2. Протоиерей Николай Артемов. К Всезарубежному Собору 2006 года. http://www.pravoslavie.ru/5441.html

3. Положение О Русской Православной Церкви Заграницей. http://sinod.ruschurchabroad.org/Arh%20Sobor%201964%20Polojenie%20o%20ROCOR.htm

4. С.В. Троицкий. Размежевание или Раскол. YMCA Press. Paris 1932

5. Архивные Документы Священномученика Кирилла (Смирнова). Доклад Отдела о Высшем Церковном Управлении о церковных округах на Священном соборе 1917-1918 гг. http://pstgu.ru/download/1172600253.scshmch_kirill.pdf

6. Протоиерей Николай Артемов. Постановление № 362 от 7/20 ноября 1920 г. и закрытие зарубежного ВВЦУ в мае 1922 г. http://www.anti-raskol.ru/pages/2514

7. Владимир Русак. Зарубежная Церковь и митрополит Сергий. http://www.apocalyptism.ru/Rusak.Russian-Church-2.htm

8. А.В. Попов. История русских зарубежных церковных разделений в ХХ веке. http://www.anti-raskol.ru/pages/2535

9. Владимир Русак. Русская Зарубежная Церковь. http://www.apocalyptism.ru/Rusak.Russian-Church-1.htm

10. М.В. Шкаровский. Возникновение Русской Православной Церкви Заграницей и Религиозная Жизнь Российских Эмигрантов в Югославии. http://christian-reading.info/data/2012/04/2012-04-04.pdf

11. Епископ Григорий (Граббе). Русская Церковь перед лицом господствующего зла. http://simvol-veri.ru/xp/russkaya-cerkov-pered-licom-gospodstvuyushego-zla.html

12. Протоиерей Михаил Польский. Каноническое положение высшей церковной власти в СССР и заграницей. http://omolenko.com/otstuplenie/polsky.htm?p=all

13. Еп. Григорий (Граббе). Церковь и Ее Учение в Жизни. том 1-й. Монреаль 1964

14. Деяния Священного Собора Православной Российской Церкви 1917-1918 гг. Том 11-й. Деяния 168-169.

15. Временное Положение о Русской Православной Церкви заграницей. 1936 г. http://sinod.ruschurchabroad.org/Arh%20Sobor%201936%20Vremennoe%20polojenie.htm

16. Протопресвитер Георгий Граббе. Правда о Русской Церкви на Родине и за Рубежом. Jordanville, N.Y., 1961

17. Постановление Святейшего Патриарха, Священного Синода и Высшего Церковного Совета Православной Российской Церкви от 7/20 ноября 1920 года за № 362. http://www.synod.com/synod/documents/ukaz_362.html

18. Лекция прот. Г. Митрофанова. «История Церкви ХХ века сквозь призму личности Патриарха Тихона» http://www.pravmir.ru/istoriya-tserkvi-hh-veka-skvoz-prizmu-lichnosti-patriarha-tihona-vtoraya-lektsiya/

19. ДЕЯНИЯ РУССКОГО ВСЕЗАГРАНИЧНОГО ЦЕРКОВНОГО СОБОРА 21 ноября – 3 декабря 1921 года в Сремских Карловцах http://sinod.ruschurchabroad.org/Arh%20Sobor%201921%201%20vsezarub%20deyaniya.htm

Сокращенная версия этого доклада имеется здесь

Ukase № 362 and Church Districts

Hegumen Andrei (Erastov)

January 2017

Introduction

The vessel that is the ROCA was shipwrecked in 2007, with very few avoiding drowning by taking to the lifeboats – the “fragments” of the former Church Abroad.

Almost 10 years have passed since then, and we find ourselves in complete crisis. The situation is so bleak, that many now say openly that the Church Abroad no longer exists and that the time may have come to join a different jurisdiction.

What is the reason for this crisis situation? Our primary problem is the lack of understanding of who we are and what our canonical status is as a church. We live in the paradigms of the past, as if nothing has happened, as if the ship did not founder and instead sails on as before. Also, those floating in their lifeboats believe that only their vessel is the one of the past.

Despite the absurdity of such a viewpoint, that is the official ecclesiology of many of the “fragments.” Above all else, the lack of a clear, canonical self-definition divides us and hampers the Church from its important role, to be a witness for the truth.

This theme, that is the clarification of our canonical status, is the purpose of this report.

Ukase №362

In accordance with the Status of the ROCA, “The Russian Orthodox Church Abroad is an indivisible part of the Local Russian Orthodox Church, temporarily self-governing on conciliar principles until the removal of the atheistic power of Russia, in accordance with the resolution of the Holy Patriarch, the Holy Synod and the Supreme Ecclesiastical Council of the Russian Church of November 7/20, 1920, №362.” (1)

Therefore the Resolution of November 7/20, 1920, №362, usually called for short Ukase №362 of Pat. Tikhon, is the canonical foundation of the ROCA.

Ukase №362 has great meaning for the entire Russian Church, and especially for the ROCA. The ukase was issued by all three parts of the supreme church authority: Pat. Tikhon, the Holy Synod and the Supreme Ecclesiastical Council.

Upon initial examination, Ukase №362 addresses only a specific set of circumstances during the Russian Civil War, when many dioceses were cut off from Moscow by the war front, but actually, the significance of Ukase №362 is much greater. This becomes clearer, if we analyze not only the text of the Ukase, but also the circumstances in which it was issued.

Towards the end of November 1920, the Civil War was almost over with the Bolsheviks claiming victory. It was becoming clear that the Soviet government was here to stay for a long time, for many years. Persecution of the Church increased, with the Bolsheviks issuing one anti-religious ukase after another.

At the same time, the power and authority of the Holy Synod and Supreme Ecclesiastical Council were coming to an end. Pursuant to the resolution of the Local Council of 1917-18, the supreme church authority was made up of three parts: the Patriarch, the Holy Synod and the Supreme Ecclesiastical Council (the last handled administrative matters and included members of clergy and laypeople). Members of the Holy Synod and the Supreme Ecclesiastical Council were elected for three-year terms until the next Local Council, which was to be convened every three years. It became obvious that the Soviets would not allow a new Local Council to be convened, and therefore, it would not be possible to elect new members for the Holy Synod and SEA. Also, in case the Holy Patriarch were to die, it would not be possible to elect a new patriarch.

These circumstances are anticipated in Ukase № 362, by the clauses, for example, “if the Holy Synod and the Supreme Ecclesiastical Council cease to exist for whatever reason,” or if the “Supreme Church Authority led by the Holy Patriarch can no longer fulfill its duties.”

As the authors of the Ukase predicted, the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority of the Russian Church soon ceased to function, temporarily at first in 1922 during the time of Renovationism, and then later in 1927, the Soviets were able to bring the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority under its control.

Thus, Ukase №362 provides general ruling principles of how the canonical, conciliar life of the Russian Church must be arranged if the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority is not present for one or another reason. We do not recognize the canonicity of the church authority of the Moscow Patriarchia, therefore, Ukase №362 is the primary canonical act of the Russian Church, upon which our life in the church must be based. No one has or can revoke this Ukase, as there is no body which could do so, ie. a Local Council of a free Russian Church.

The second and third clauses of the Ukase are most relevant for the ROCA:

2) If as a result of the front being moved, borders being changed, etc., a diocese finds itself cut off from a Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority or the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority headed by the Holy Patriarch itself ceases to function, the diocesan bishop immediately joins with the bishops of neighboring dioceses in order to form a Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority body overseeing several dioceses that are all in the same situation (forming either a Provisional Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority or a metropolitan district or something else).

3) The duty to form the Supreme Church Authority for a whole group that finds itself in the situation described in clause № 2 falls to the bishop most senior by ordination.

This way, if several dioceses are unable to connect to the church center, the Ukase provisions the creation of an administrative body that is temporarily autonomous, like a metropolitan district, for example.

The primary goal of these provisions is conciliarity, as evidenced especially in the fifth and sixth clauses of Ukase №362. The fifth clause describes a situation of when a diocese is cut off from the center, but the bishop is unable to contact bishops of any of the neighboring dioceses. Since a diocese can only have one ruling bishop, then a diocese that is cut off from the heart of the church loses its conciliarity. In such a case, the Ukase recommends dividing this diocese into several dioceses and provide the vicars with the rights of an independent bishop, ie. create a council of bishops. In this way the dividing transforms, “a diocese into a church district led by a bishop in the main city of the diocese, and this church district will administer local church matters in agreement with the canons .” (Clause № 6)

Metropolitan Districts

Let us consider the question of a “church” or “metropolitan” district. A metropolitan district is a foundational canonical body. At the time of the First Ecumenical Council (325 AD), the Church located within the Roman Empire was comprised of many autocephalous metropolitan districts. (3) These small autocephalous Churches were made up of several small dioceses and were found usually within the borders of the Roman provinces. They were headed by a metropolitan, i.e. a bishop of the metropolis, the main city of the province. (4) A metropolitan district was independent and autocephalous, i.e. a council of bishops of the metropolis elected a metropolitan for themselves.

The canonical order of a metropolitan district is described in rule 34 of the Apostles’ canons:

“The bishops of every nation (in the sense of region or province) must acknowledge him who is first among them and account him as their head, and do nothing of consequence without his consent; but each may do those things only which concern his own diocese, and the country places which belong to it. But neither let him who is the first do anything without the consent of all the bishops; for so there will be unanimity, and God will be glorified through the Lord in the Holy Spirit, the Father, the Son and Holy Spirit.”

This rule of the Apostles symbolizes the conciliar order of the Church. Diocesan bishops may not do anything that exceeds their customary authority without the agreement of the First Hierarch, though the First Hierarch is not an autocrat. He must defer to the “agreement of all,” i.e. the decisions of the Council of Bishops of his region.

At the time of the First Ecumenical Council there were almost one hundred metropolitan districts in the Roman empire. (5) (This figure can be determined by the number of provinces in the Empire. If there were about 1,800 bishops at the time of the First Ecumenical Council, then there were about 18 bishops in each district. (Wikipedia))

Our customary understanding of the Church is that there is one autocephalous church in each Orthodox country. Let us note this fact, which is so unusual for us, that in one state, the Roman Empire, the Church at the beginning of the 4th century was made up of a family of small autocephalous churches, almost one hundred in number. These autocephalous churches were not united on an administrative level, yet the sense of the unity of the conciliar Church was much stronger than it is today. When there was an urgent need, bishops from several regions met in councils, and of course, in ecumenical councils.

It is interesting to note this divided state of the administration of the Church existed in the pagan era while under persecution, and when the Empire became Christian the administrative structure of the Church grew larger, as the process began of uniting the autocephalous metropolitan districts into patriarchates. This union, though, was not driven by the canons, but by everyday needs. The process of uniting administratively was slowed by the canons. (6) Not only were the metropolitan districts not dissolved by the canon rules, but just the opposite, they demanded their continued existence. (7)

The Local Council of 1917-1918

The Russian Church was never divided into districts. From the beginning, the Russian Church was formed as one metropolitan district, with the metropolitan of Kiev (and later Moscow) as its head. The requirement of conciliarity as stipulated in rule 34 of the Apostles’ canons was carried out by the Russian bishops in their obedience to the Metropolitan and later the Patriarch of All-Russia. (8)

After Emperor Peter abolished the patriarchate and replaced it with the Holy Synod (in 1721), the canonical order was severely affected. Instead of a senior bishop at the head of the Church, a faceless synod chancellery was established under the supervision of a government functionary, the Chief Procurator. The Church was organized in such a way that it became one of the departments of the regime. The principle of conciliarity as realized in the council of bishops disappeared almost completely in the Russian Church during the synod period.

This state of affairs lasted until the Local Council of 1917-1918, when the patriarchate was restored. Those involved in the Local Council were concerned that the Patriarch would be unable to have personal contact with the bishops, because of the large number of dioceses (about 70) in the Russian Church at the time, and thus would not have a clear understanding of matters in each diocese. They feared that conciliarity would not return to church life, and that the synod chancellery would simply be replaced by a chancellery of the patriarch, that would be swamped by clerical matters. An intermediary between the supreme ecclesiastical authority and the dioceses would need to be found. The metropolitan districts were meant to serve just that purpose. As was said at the Council, “The conciliarity of the bishops would not exist without the councils of the metropolitan districts. A revival of church life in the dioceses would not occur while they were isolated from each other. The supreme ecclesiastical authority is not able to rule on its own, concentrating all power for itself at the center. Most matters need to be decided locally.” (9)

It was decided to create metropolitan districts from a small number of dioceses in each district. The assembling of dioceses into districts took into account such factors as the circumstances of church life, the ease of communication, the particular local administrative parts and others. (10)

Holy Martyr Met. Kirill (Smirnov) presented the topic of metropolitan districts at the Council. He said in his report, “The varied vested interests and everyday way of life in the many corners of the vast Russian land require that church districts not contain too many dioceses. It would be hard, for example, to include even all of the Volga region in one district, since life and church needs are far from the same in Kazan, for example, and in Astrakhan, nor are they the same in the wide open spaces of Siberia.”

Councils in the districts had the following functions: determine matters important to the dioceses of the district that needed to be addressed at the Local Council, to recommend to the Holy Patriarch which new independent dioceses need to be created in the district; take part in the assignment of bishops to open cathedras and conduct the cheirotonia of candidates selected and approved by the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority, to consider the canonization of saints to be venerated locally and many other things.

The metropolitan of a district was to: convene and chair councils in the district, to report the outcome of these councils to the Holy Patriarch and other matters.

One of the arguments of opponents of the creation of metropolitan districts was that this innovation may lead to separatism. A counter-argument was that forced centralization, and not decentralization, would lead in large part to separatism.

It is important to note the difference between the metropolitan districts of the ancient Church and those introduced by the Local Council. It is that the latter were not autocephalous and answered to the supreme ecclesiastical authority.

The resolutions of the Local Council adopted on September 6/19, 1918, included the following, “Since the absence of church districts can be considered an existing shortcoming of the Russian Church…and considering the number of dioceses headed by the Patriarch…the Holy Council approves the creation of church districts with the goal of establishing a complete canonical structure in the Russian Church, while the number of districts and determining the makeup of dioceses in the districts will be decided by the Supreme Ecclesiastical Council.” (11)

Unfortunately, political factors did not allow bringing this decision of the Local Council to life. After the civil war, the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority of the Russian Church was unable to contact more than half of the dioceses. It would be senseless in those circumstances to decide the borders of church districts. Dioceses cut off from Moscow began themselves to create temporary bodies of the church administration. Ukase №362 was developed in this historical setting. It embodies those aspects of church life experienced in the areas cut off from the center by the civil war. In general, it is commonplace that rules of the church confirm established practices. In many respects, it was like that in ancient times as well.

We have provided a detailed explanation of the decisions of the Local Council regarding the metropolitan districts, since Ukase №362 cannot be understood properly without considering them.

Ukase №362 and the Church Abroad

The basis of the future ROCA was the Provisional Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority of the South-East Russia (PSEA) established in 1919 on the territory occupied by the army of Gen. Denikin. After evacuating from the Crimea in 1920, it continued its work under the name of the SREA (Supreme Russian Ecclesiastical Authority). The first session (outside of Russia) of the SREA was held on November 6/19, 1920, on the ship “Great Prince Aleksandr Mikhaylovich” in the Bosphorus Strait. The following Archpastors took part in the session: Met. Antony (Khrapovitskiy), Met. Platon (Rozhdestvenskiy), Archbishop Theophan (Bystrov) and others.

The creation of a supreme ecclesiastical authority was so greatly welcomed by the church at the time that almost all the bishops abroad (there were over 30 bishops) recognized the SREA. (After 1922, it was renamed the Provisional Synod of Bishops Abroad.) (12) That was at the beginning, but with time centrifugal forces increased and divisions occurred (in 1926).

Ukase №362 was issued on November 7/20, 1920, (that is, a day after the first session abroad of the SREA), but became known abroad only in the beginning of 1922. Therefore, the canonical structure of the ROCA was established before Ukase №362 became known to the bishops of the ROCA. That explains why, in part, the structure does not exactly conform to the letter of this Ukase. The ROCA was established on the basis of Ukase №362 in the sense, that because they were cut off from the central ecclesiastical authority, the bishops abroad were able to create a supreme ecclesiastical authority, though the structure of this authority did not conform completely to Ukase №362.

Indeed, Ukase №362 anticipates the possibility of several dioceses being cut off from the central supreme ecclesiastical authority or even the possibility of this authority ceasing to exist, and directs the dioceses that find themselves in these circumstances to organize conciliar structures like metropolitan districts, but is silent about the possibility of the creation of a some sort of common supreme ecclesiastical authority overseeing several such districts. In other words, the Ukase does not foresee the creation of a common central church authority for all of the diaspora, like the one that was created in Sremski Karlovci.

The concept of those who established the ROCA is apparent in the resolution of the First All-Diaspora Council (November, 1921) regarding a “Supreme Russian Ecclesiastical Authority abroad.” (Remember, Ukase №362 was not known at that time abroad.) Pursuant to this resolution, the SREA was an exact mirror image of the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority in Russia. It was to be led by a locum tenens of the Patriarch and composed of the Russian Synod Abroad and the Ecclesiastical Council. (38) Patriarch Tikhon though did not approve the naming of a locum tenens abroad. Thus, in the way the founders conceived it, the SREA was not the authority over one metropolitan district, but as its name denotes, it was the supreme ecclesiastical authority for the part of the Russian Church abroad free of the Bolsheviks.

The Synod in Karlovci was accused of aspiring to play the role of an All-Russia Holy Synod, though it had no approval from the supreme ecclesiastical authority. (13) Strictly speaking, these charges were warranted, but it must be noted that the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority in Russia under Pat. Tikhon was not free, and then later under Met. Sergey, it became an instrument of influence for the Bolsheviks. On the contrary, the ROCA Synod saw itself as the ecclesiastical authority of the free part of the Russian Church. This led though to the idea among the episcopate abroad that the Synod abroad led by Met. Antony can represent the entire Russian Church, and even in case the SEA in Russia ceases to exist, cannot only head the part of the Church abroad, but the entire Russian Church from outside of Russia. For example, after the death of Holy Patriarch Tikhon, the Synod decided on April 9, 1925: “To give the Chairman of the Synod of Bishops, Met. Antony, the right temporarily, until a canonical All-Russia Ecclesiastical Council can be convened, to be the locum tenens of the Patriarch and to lead the All-Russia Orthodox Church, and as conditions and circumstances allow, to direct the life of the Church not only outside of Russia, but in Russia as well.” (14)

This view of the ROCA as the free voice of the Russian Church existed until very recently, right before its union with the MP.

Opponents of the Karlovci Synod, Met. Evlogiy, Prof. S. Troitskiy and others, charged that the attempts of Met. Antony and his associates to solidify the central church authority abroad were not necessary and even harmful to the Church. This view is certainly completely misguided. The existence of the Synod was justified by its high spiritual authority and the authority of its First Hierarch. In a sermon at the Russian Holy Trinity church in Belgrade, the Serbian Patriarch Varnava said, “You have among you Met. Antony. This great hierarch is an adornment of the Ecumenical Orthodox Church. His great mind is like that of the first bishops of Christ’s Church at the beginning of Christianity. He represents the truth of the church. All of you, not only those living in our Yugoslavia, but those living in Europe, in America, in Asia and all the countries of the world must present, with your great archpastor Met. Antony at the head, an indivisible whole, resistant to attacks and provocations of the enemies of the Church.” (15)

Actually, legally, the ROCA Synod was not sanctioned by the supreme ecclesiastical authority of the Russian Church. In fact, the SREA was later dissolved by Ukase № 348 of Pat. Tikhon on May 5, 1922. That same year a council of bishops that gathered in Sremski Karlovci officially carried out the will of Patriarch Tikhon and dissolved the Supreme Russian Ecclesiastical Authority, but since they suspected that the First Hierarch’s ukase was issued under duress by the Soviet regime, decided instead to form a Provisional Synod of Bishops Abroad, which also was not approved by the Patriarch.

Undoubtedly, Ukase № 348 was issued under pressure from the Bolsheviks, but in issuing this ukase, Holy Patriarch Tikhon was hoping for what actually transpired, that the bishops abroad would not obey this ukase. In large part, the life of the Church is not dictated by the exact letter of the ukases and canons. On the contrary, the canons affirm and approve the church structure that arises from life’s circumstances. If not, the ukases are no more than words written on paper and do not influence the life of the Church.

The united center of the church abroad was formed not by the base pretentions and lust for power of some disparate people, as its critics charged, but by life itself and was animated by conscience of bishops, and not by the letter of Ukases. The words of the church historian Prof. V. Bolotov are well known, “That which is good for the Church is what should be considered canonical.”

However, Ukase №362 does not sanction one church center abroad, and there are no other canonical statutes which would sanction its formation.

The majority of the bishops abroad freely obeyed the SREA, as they didn’t understand how the church could exist without a unified church administration. Metropolitan districts were a recent innovation of the Local Council of the Russian Church, which had not been yet implemented anywhere and thus many were not familiar with the idea.

To show how the Russian episcopate had not absorbed the idea of metropolitan districts as proposed by the Local Council and Ukase №362, it is enough to provide the following example. A scheduled session of the Council of Bishops took place in 1923 in Sremski Karlovci. Those bishops unable to attend the council received a list of questions, the first among them, “Do you consider it necessary to have a supreme church body to administer the dioceses abroad or do you consider it possible that the bishops govern their dioceses themselves, autonomously?” (17) This question presents only two choices; the existence of one supreme ecclesiastical authority or the complete division of all the dioceses into separate parts. The possibility of uniting several dioceses into a church district is not even considered. In general, one notices in the arguments of the supporters of one church center abroad and their opponents, that the former do not completely understand the idea of metropolitan districts. To that end, it is interesting to consider the argument between Prof. S. Troitskiy and G. Grabbe.

The Argument between S. Troitskiy and G. Grabbe

Professor S.V. Troitskiy, the most authoritative canon law expert in the diaspora, in 1932 published the book “Delimitation or Schism,” in which he accused the Synod in Sremski Karlovci of illegitimate ambitions to lead the entire Russian diaspora. He considered these pretensions to authority to be the main reason for the divisions in the ROCA that occurred in the mid-1920s. G. Grabbe, the future Bishop Gregory, the secretary of the Synod, responded to Troitskiy in the same year in the article “Unity or Fragmentation.” It is interesting to examine this duel between two very formidable opponents.

Troitskiy, a participant in the Local Council (he served as the secretary of the Chancellery of the Local Council and his signature is on the Report on Church Districts presented by St. Kirill (18)), argued that “the precise execution of Ukase №362 would entail the organization abroad of several temporary autonomous metropolitan districts, led and guided by their diocesan bishops’ councils under the leadership of the district metropolitans.”(18)

He envisioned four such districts: the West European, the Near Eastern (this referred to Eastern Europe), the North American, and the Far Eastern.

“Such a delimitation (i.e. into four districts) does not preclude the possibility of forming general councils of bishops of these districts (only to address issues of extreme importance) but it is not necessary to create a permanent body of a Higher Church Administration in the form of a Synod, a Supreme Church Council and so on.”(19)

“All of the diaspora parts of the Russian Orthodox Church, divided into several autonomous metropolitan districts and united through a periodically convened General Council, would live in peace and tranquility.” (20) “The desire to preserve an uninterrupted unity of church administration, a sort of ecclesiastical imperialism, is the major cause of the strife within the Church.” (21)

Ukase №362 prescribes that when a diocese is cut off from the center, the diocesan bishop should establish relations with bishops in neighboring dioceses for the purpose of organizing a higher level of ecclesiastical authority for those several dioceses that find themselves in similar circumstances.

In Prof. Troitskiy’s opinion, the entire diaspora could not be organized as one metropolitan district, because all of the dioceses of the Russian diaspora could not be considered as “finding themselves in similar circumstances.” He argued: “Indeed, is it possible to call the Russian dioceses of Yugoslavia, China and America, neighbors who find themselves in similar circumstances?”(22) It is difficult to regard dioceses as being in similar circumstances when they are located at such great distances from each other. Their only similar circumstance was their independent position in relation to Bolshevik Russia.

The status of Russian people living in different countries, in different political systems, in different parts of the world, was very diverse. And as we remember, in the discussion at the Local Council of the issue of assigning dioceses of the Russian Church into Metropolitan Districts, it was important to first and foremost take into account the general needs of the population and the ease of communication between dioceses. For example, St. Met. Kirill’s report to the Local Council provided an approximate plan for dividing the dioceses of the Russian Church into Metropolitan Districts. In accord with this division, the North American dioceses constituted one district, which, of course, did not include all of the dioceses in the diaspora.(23)

G. Grabbe objected to Troitskiy’s views by stating: “If all the bishops are in agreement and wish to unite, then why not do so? If each separate, isolated diocese has the right to form a higher Church Administration or a Metropolitan District, then by what logic does Mr. Troitskiy contest the same right for all of the dioceses as a whole? The moral weight of a united Russian Church, in any case, will always be greater than the weight of the Church in fragmented form.”(24) “It is also strange to speak of the impossibility of having a single center for the whole of the Church Abroad when such a center has already existed for more than 10 years.”(25) “The SREA united all of the diaspora dioceses … This association, however, was not yet based on the Resolution of 1920 (Ukase №362) because the existence of the Ukase was not yet known, but a sound awareness of the Church’s needs prompted the conclusion that the Church Abroad must be united and that this unity has a considerable weight, which can also be of benefit to our persecuted brothers in Russia.”(26) “The good of the Church does not require fragmentation and moreover this would not be painless as the vast majority of Russian bishops believe it to be impossible and unnecessary.”(27)

G. Grabbe convincingly argues in favor of uniting all of the diaspora parts of the Russian Church. He justifies the existence of the Synod on considerations of benefit to the church and on the fact that it was established by the needs of life itself and thus accepted as an expression of the Church by most of the bishops. However, G. Grabbe does not have strong arguments against S. Troitskiy’s assertions that a united Church center abroad does not conform to the letter or spirit of Ukase №362. Even if it is possible, with some stretching, to justify such a center based on Ukase №362, then to be fair the converse must also be true, i.e. if the diaspora was initially organized into several church districts, then based on Ukase №362, it would be impossible to require their subordination to a single center.

Metropolitan Antony himself considered ROCA to be a single metropolitan district. He wrote to Metropolitan Elevferiy of Lithuania in 1934 that “a temporary metropolitan district has long been established abroad, based on the Ukase of 7/20 November 1920, with me as its leader.”(28)

If the ROCA was a union of dioceses into one metropolitan district, then how to explain the fact that within the ROCA smaller metropolitan districts had been separated out? In this fashion the Western European diocese, by a decision of the Council of Bishops in 1923, had been separated into an autonomous metropolitan district.

In 1935 the Council of Bishops attempted to overcome the divisions in the church by creating metropolitan districts. In accord with the Provisional Regulations of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad of 1936, four metropolitan districts were formed consisting of several dioceses. The districts chose their Metropolitan and submitted candidates for episcopal consecration for approval to the Synod. Thus the districts were only partially autonomous and were subordinate to the Karlovci Synod. Thus, the Provisional Regulations were a compromise that preserved both centralization and partial autonomy for the districts. Among the creators of this Regulation were Prof. S. Troitskiy and G. Grabbe.(29)

The 1936 Provisional Regulations very closely followed the canonical formulation of the metropolitan districts that was worked out at the 1918 Local Council. The only difference was that in the 1936 Regulations the metropolitan districts were subordinate to the ROCA Synod, while the metropolitan districts approved by the Local Council were subordinate to the Supreme Russian Church authority.

As a result it is quite obvious that the ROCA Synod was not a single metropolitan district in accordance with Ukase №362, but rather an alternative form of a supreme ecclesiastical authority. However, Ukase №362 says nothing about creating a church center to which several church districts would be subordinated. The Ukase did not foresee or prescribe such a development. The absence of a supreme ecclesiastical authority does not mean that anyone can assume this authority without the sanction of the supreme ecclesiastical authority.