(This is an abridged version of the report delivered at the VI All-Diaspora Council in January 2017.)

Introduction

The vessel that is the ROCA was shipwrecked in 2007, with very few avoiding drowning by taking to the lifeboats – the “fragments” of the former Church Abroad.

Almost 10 years have passed since then, and we find ourselves in complete crisis. The situation is so bleak, that many now say openly that the Church Abroad no longer exists and that the time may have come to join a different jurisdiction.

What is the reason for this crisis situation? Our primary problem is the lack of understanding of who we are and what our canonical status is as a church. We live in the paradigms of the past as if nothing has happened as if the ship did not founder and instead sails on as before. Also, those floating in their lifeboats believe that only their vessel is the one of the past.

Despite the absurdity of such a viewpoint, that is the official ecclesiology of many of the “fragments.” Above all else, the lack of a clear, canonical self-definition divides us and hampers the Church from its important role, to be a witness for the truth.

This theme, that is the clarification of our canonical status, is the purpose of this report.

Ukase №362

In accordance with the Status of the ROCA, the Resolution of the Holy Patriarch, the Holy Synod and the Supreme Ecclesiastical Council of the Russian Church of November 20, 1920, №362, usually called for short Ukase №362 of Pat. Tikhon is the canonical foundation of the ROCA.

Upon initial examination, Ukase №362 addresses only a specific set of circumstances during the Russian Civil War, when many dioceses were cut off from Moscow by the war front, but actually, the significance of Ukase №362 is much greater. This becomes clearer if we analyze not only the text of the Ukase but also the circumstances in which it was issued.

Towards the end of November 1920, the Civil War was almost over with the Bolsheviks claiming victory. It was becoming clear that the Soviet government was here to stay for a long time, for many years. Persecution of the Church increased, with the Bolsheviks issuing one anti-religious ukase after another.

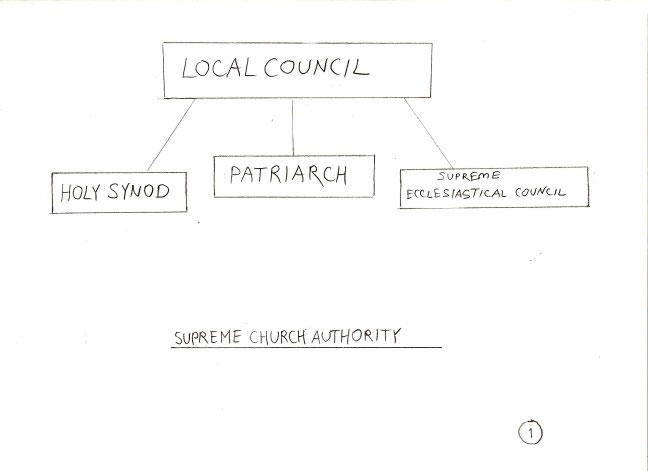

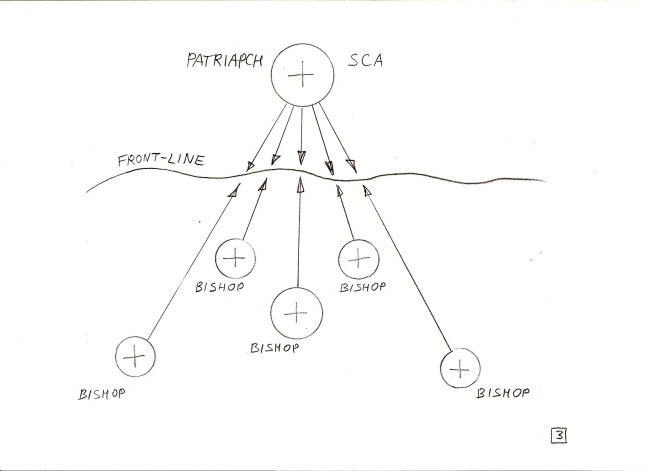

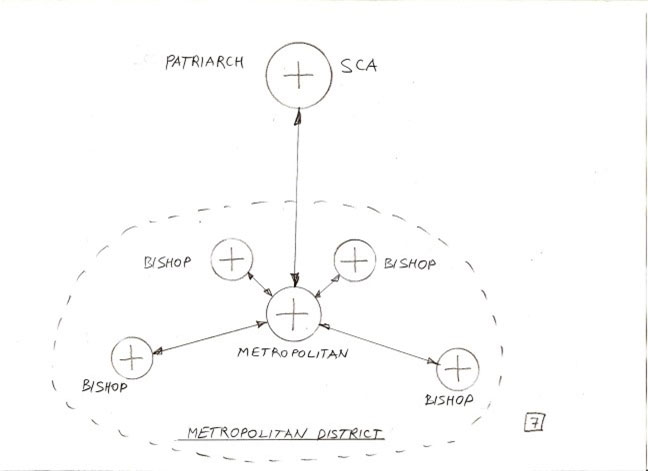

At the same time, the power and authority of the Holy Synod and Supreme Ecclesiastical Council were coming to an end. Pursuant to the resolution of the Local Council of 1917-18, the supreme church authority was made up of three parts: the Patriarch, the Holy Synod and the Supreme Ecclesiastical Council (the last handled administrative matters and included members of clergy and laypeople). Members of the Holy Synod and the Supreme Ecclesiastical Council were elected for three-year terms until the next Local Council, which was to be convened every three years. (Drawing 1) It became obvious that the Soviets would not allow a new Local Council to be convened, and therefore, it would not be possible to elect new members for the Holy Synod and SEA. Also, in case the Holy Patriarch were to die, it would not be possible to elect a new patriarch.

These circumstances are anticipated in Ukase № 362, by the clauses, for example, “if the Holy Synod and the Supreme Ecclesiastical Council cease to exist for whatever reason,” or if the “Supreme Church Authority led by the Holy Patriarch can no longer fulfill its duties.”

As the authors of the Ukase predicted, the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority of the Russian Church soon ceased to function, temporarily at first in 1922 during the time of Renovationism, and then later in 1927, the Soviets were able to bring the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority under its control.

Thus, Ukase №362 provides general ruling principles of how the canonical, conciliar life of the Russian Church must be arranged if the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority is not present for one or another reason.

We do not recognize the canonicity of the church authority of the Moscow Patriarchia, therefore, Ukase №362 is the primary canonical act of the Russian Church, upon which our life in the church must be based. No one has or can revoke this Ukase, as there is no body which could do so, ie. a Local Council of a free Russian Church.

The second and third clauses of the Ukase are most relevant for the ROCA:

2) If as a result of the front being moved, borders being changed, etc., a diocese finds itself cut off from a Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority or the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority headed by the Holy Patriarch itself ceases to function, the diocesan bishop immediately joins with the bishops of neighboring dioceses in order to form a Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority body overseeing several dioceses that are all in the same situation (forming either a Provisional Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority or a metropolitan district or something else).

3) The duty to form the Supreme Church Authority for a whole group that finds itself in the situation described in clause № 2 falls to the bishop most senior by ordination.

This way, if several dioceses are unable to connect to the church center, the Ukase provisions the creation of an administrative body that is temporarily autonomous, like a metropolitan district, for example.

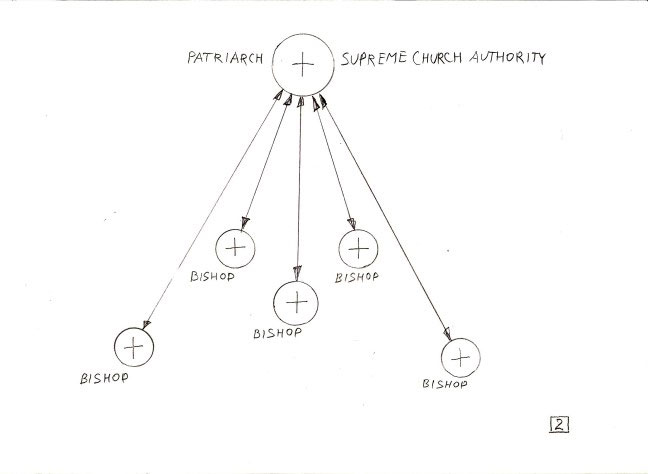

The primary goal of these provisions is conciliarity. It should be mentioned that Russian Church was centralized to a great extent. The conciliar relations existed only between the Supreme Church Authority and every single diocese, while between neighboring dioceses there were no conciliar ties. (Drawing 2)

Therefore if a diocese were cut off from the center it would totally lose conciliarity. (Drawing 3)

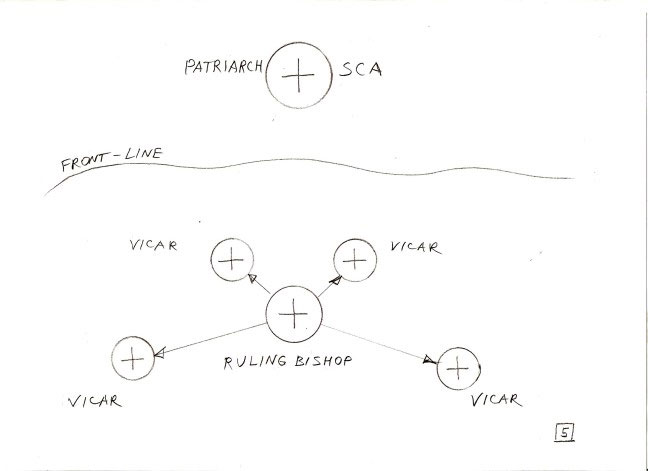

That the primary goal of the Ukase №362 is conciliarity is evidenced especially in the fifth and sixth clauses of Ukase. The fifth clause describes a situation of when a diocese is cut off from the center, but the bishop is unable to contact bishops of any of the neighboring dioceses. Since a diocese can only have one ruling bishop, then a diocese that is cut off from the heart of the church loses its conciliarity. (Drawing 5)

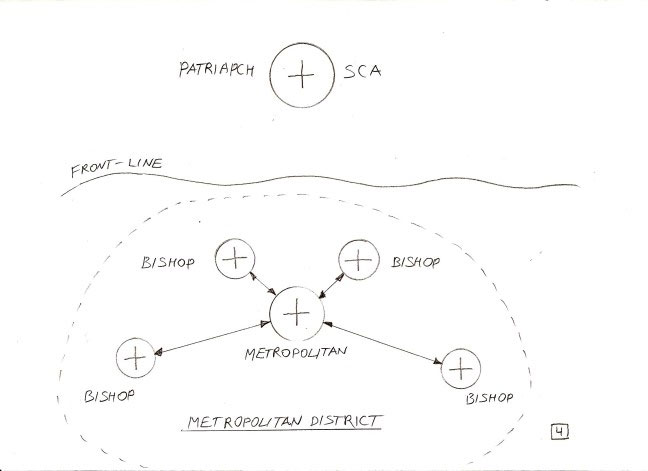

In such a case, the Ukase recommends dividing this diocese into several dioceses and provide the vicars with the rights of an independent bishop, ie. create a council of bishops. In this way the dividing transforms, “a diocese into a church district led by a bishop in the main city of the diocese, and this church district will administer local church matters in agreement with the canons .” (Clause № 6) (Drawing 4)

Metropolitan Districts

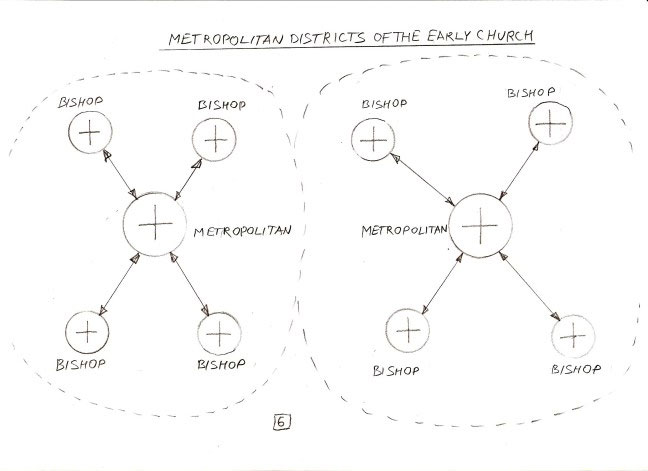

Let us consider the question of a “church” or “metropolitan” district. A metropolitan district is a foundational canonical body. At the time of the First Ecumenical Council (325 AD), the Church located within the Roman Empire was comprised of many autocephalous metropolitan districts. These small autocephalous Churches were made up of several small dioceses and were found usually within the borders of the Roman provinces. They were headed by a metropolitan, i.e. a bishop of the metropolis, the main city of the province. A metropolitan district was independent and autocephalous, i.e. a council of bishops of the metropolis elected a metropolitan for themselves.

The canonical order of a metropolitan district is described in rule 34 of the Apostles’ canons:

“The bishops of every nation (in the sense of region or province) must acknowledge him who is first among them and account him as their head, and do nothing of consequence without his consent; but each may do those things only which concern his own diocese, and the country places which belong to it. But neither let him who is the first do anything without the consent of all the bishops; for so there will be unanimity, and God will be glorified through the Lord in the Holy Spirit, the Father, the Son and Holy Spirit.”

This rule of the Apostles symbolizes the conciliar order of the Church. Diocesan bishops may not do anything that exceeds their customary authority without the agreement of the First Hierarch, though the First Hierarch is not an autocrat. He must defer to the “agreement of all,” i.e. the decisions of the Council of Bishops of his region. (Drawing 6)

At the time of the First Ecumenical Council, there were almost one hundred metropolitan districts in the Roman Empire. (This figure can be determined by the number of provinces in the Empire.)

Our customary understanding of the Church is that there is one autocephalous church in each Orthodox country. Let us note this fact, which is so unusual for us, that in one state, the Roman Empire, the Church at the beginning of the 4th century was made up of a family of small autocephalous churches, almost one hundred in number. These autocephalous churches were not united on an administrative level, yet the sense of the unity of the conciliar Church was much stronger than it is today. When there was an urgent need, bishops from several regions met in councils, and of course, in ecumenical councils.

It is interesting to note this divided state of the administration of the Church existed in the pagan era while under persecution, and when the Empire became Christian the administrative structure of the Church grew larger, as the process began of uniting the autocephalous metropolitan districts into patriarchates.

The Local Council of 1917-1918

The Russian Church was never divided into districts. From the beginning, the Russian Church was formed as one metropolitan district, with the Metropolitan of Kiev (and later Moscow) as its head. The requirement of conciliarity as stipulated in rule 34 of the Apostles’ canons was carried out by the Russian bishops in their obedience to the Metropolitan and later the Patriarch of All-Russia.

After Emperor Peter abolished the patriarchate and replaced it with the Holy Synod (in 1721), the canonical order was severely affected. Instead of a senior bishop at the head of the Church, a faceless synod chancellery was established under the supervision of a government functionary, the Chief Procurator. The Church was organized in such a way that it became one of the departments of the regime. The principle of conciliarity as realized in the council of bishops disappeared almost completely in the Russian Church during the synod period

This state of affairs lasted until the Local Council of 1917-1918 when the patriarchate was restored. Those involved in the Local Council were concerned that the Patriarch would be unable to have personal contact with the bishops, because of the large number of dioceses (about 70) in the Russian Church at the time, and thus would not have a clear understanding of matters in each diocese. They feared that conciliarity would not return to church life and that the synod chancellery would simply be replaced by a chancellery of the patriarch, that would be swamped by clerical matters.

An intermediary between the supreme ecclesiastical authority and the dioceses would need to be found. The metropolitan districts were meant to serve just that purpose.

It was decided to create metropolitan districts from a small number of dioceses in each district. The assembling of dioceses into districts took into account first of all such factors as the circumstances of church life and the ease of communication.

Councils in the districts had considerable autonomy: for example, they had to assign candidates to open cathedras and conduct the cheirotonia of candidates approved by the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority.

The Metropolitan of a district was to convene and chair councils in the district.

It is important to note the difference between the metropolitan districts of the ancient Church and those introduced by the Local Council. It is that the latter were not autocephalous and answered to the supreme ecclesiastical authority. (Drawing 7)

The resolutions of the Local Council adopted on September 19, 1918, included the following, “Since the absence of church districts can be considered an existing shortcoming of the Russian Church…and considering the number of dioceses headed by the Patriarch…the Holy Council approves the creation of church districts with the goal of establishing a complete canonical structure in the Russian Church, while the number of districts and determining the makeup of dioceses in the districts will be decided by the Supreme Ecclesiastical Council.”

Unfortunately, political factors did not allow bringing this decision of the Local Council to life. After the civil war, the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority of the Russian Church was unable to contact more than half of the dioceses. It would be senseless in those circumstances to decide the borders of church districts. Dioceses cut off from Moscow began themselves to create temporary bodies of the church administration. Ukase №362 was developed in this historical setting. It embodies those aspects of church life experienced in the areas cut off from the center by the civil war. In general, it is commonplace that rules of the church confirm established practices. In many respects, it was like that in ancient times as well.

We have provided an explanation of the decisions of the Local Council regarding the Metropolitan districts since Ukase №362 cannot be understood properly without considering them

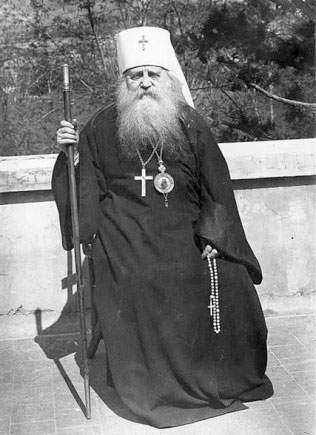

Ukase №362 and the Church Abroad

The basis of the future ROCA was the Provisional Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority of the South-East Russia (PSEA) established in 1919 on the territory occupied by the army of Gen. Denikin. After evacuating from the Crimea in 1920, it continued its work under the name of the SREA (Supreme Russian Ecclesiastical Authority). The first session (outside of Russia) of the SREA, chaired by Met. Antony (Khrapovitskiy), was held on November 19, 1920, on the ship in the Bosporus Strait.

Ukase №362 was issued on November 20, 1920, (that is, a day after the first session abroad of the SREA), but became known abroad only in the beginning of 1922. Therefore, the canonical structure of the ROCA was established before Ukase №362 became known to the bishops of the ROCA. That explains why, in part, the structure does not exactly conform to the letter of this Ukase.

Indeed, Ukase №362 anticipates the possibility of several dioceses being cut off from the central supreme ecclesiastical authority, and directs the dioceses that find themselves in these circumstances to organize conciliar structures like metropolitan districts, but is silent about the possibility of the creation of a some sort of common supreme ecclesiastical authority overseeing several such districts. In other words, the Ukase does not foresee the creation of a common central church authority for all of the diaspora, like the one that was created in Sremski Karlovci.

The Synod in Karlovci was accused of aspiring to play the role of an All-Russia Holy Synod, though it had no approval from the supreme ecclesiastical authority. Strictly speaking, these charges were warranted, but it must be noted that the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority in Russia under Pat. Tikhon was not free, and then later under Met. Sergey, it became an instrument of influence for the Bolsheviks. On the contrary, the ROCA Synod saw itself as the ecclesiastical authority of the free part of the Russian Church.

This led through to the idea among the episcopate abroad that the Synod abroad led by Met. Antony can represent the entire Russian Church, and even in case the SEA in Russia ceases to exist, cannot only head the part of the Church abroad but the entire Russian Church from outside of Russia.

This view of the ROCA as the free voice of the Russian Church existed until very recently, right before its union with the MP.

Opponents of the Karlovci Synod, Met. Evlogiy, Prof. S. Troitskiy, and others charged that the attempts of Met. Antony and his associates to solidify the central church authority abroad were not necessary and even harmful to the Church. This view is certainly completely misguided. The existence of the Synod was justified by its high spiritual authority and the authority of its First Hierarch.

Actually, legally, the ROCA Synod was not sanctioned by the supreme ecclesiastical authority of the Russian Church. In fact, the SREA was later dissolved by Ukase № 348 of Pat. Tikhon on May 5, 1922. That same year a council of bishops that gathered in Sremski Karlovci officially carried out the will of Patriarch Tikhon and dissolved the Supreme Russian Ecclesiastical Authority, but since they suspected that the First Hierarch’s ukase was issued under duress by the Soviet regime, decided instead to form a Provisional Synod of Bishops Abroad, which also was not approved by the Patriarch.

Undoubtedly, Ukase № 348 was issued under pressure from the Bolsheviks, but in issuing this ukase, Holy Patriarch Tikhon was hoping for what actually transpired, that the bishops abroad would not obey this ukase. In large part, the life of the Church is not dictated by the exact letter of the ukases and canons. On the contrary, the canons affirm and approve the church structure that arises from life’s circumstances. If not, the ukases are no more than words written on paper and do not influence the life of the Church.

The united center of the church abroad was formed not by the lust for power of some disparate people, as its critics charged, but by life itself and was animated by conscience of bishops, and not by the letter of Ukases. The words of the church historian Prof. V. Bolotov are well known, “That which is good for the Church is what should be considered canonical.”

However, Ukase №362 does not sanction one church center abroad, and there are no other canonical statutes which would sanction its formation.

The Argument between S. Troitskiy and G. Grabbe

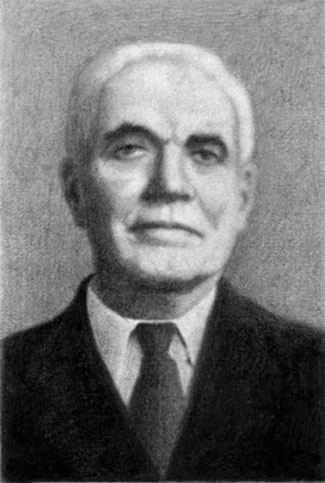

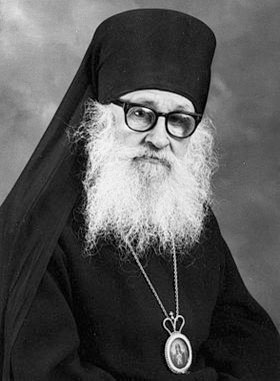

Professor S.V. Troitskiy, the most authoritative canon law expert in the diaspora, in 1932 published the book “Delimitation or Schism,” in which he accused the Synod in Sremski Karlovci of illegitimate ambitions to lead the entire Russian diaspora. He considered these pretensions to authority to be the main reason for the divisions in the ROCA that occurred in the mid-1920s. (Met. Eulogij and Met. Platon). G. Grabbe, the future Bishop Gregory, the secretary of the Synod, responded to Troitskiy in the same year in the article “Unity or Fragmentation.” It is interesting to examine this duel between two very formidable opponents.

Troitskiy argued that “the precise execution of Ukase №362 would entail the organization abroad of several temporary autonomous metropolitan districts, led and guided by their diocesan bishops’ councils under the leadership of the district metropolitans.”

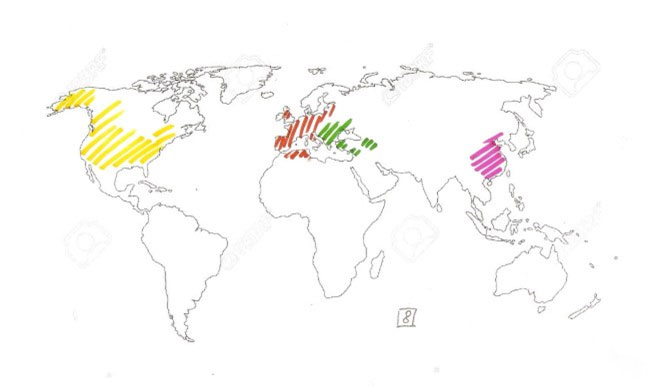

He envisioned four such districts: the West European, the East European, the North American, and the Far Eastern.

“Such a delimitation (i.e. into four districts) does not preclude the possibility of forming general councils of bishops of these districts (only to address issues of extreme importance) but it is not necessary to create a permanent body of a Higher Church Administration in the form of a Synod, a Supreme Church Council and so on.”

The status of Russian people living in different countries, in different political systems, in different parts of the world, was very diverse. And as we remember, in the discussion at the Local Council of the issue of assigning dioceses of the Russian Church into Metropolitan Districts, it was important to first and foremost take into account the general needs of the population and the ease of communication between dioceses. For example, at the Local Council there was provided an approximate plan for dividing the dioceses of the Russian Church into Metropolitan Districts. In accord with this division, the North American dioceses constituted one district, which, of course, did not include all of the dioceses in the diaspora.

- Grabbe convincingly argues in favor of uniting all of the diaspora parts of the Russian Church. He justifies the existence of the Synod on considerations of benefit to the church and on the fact that it was established by the needs of life itself and thus accepted as an expression of the Church by most of the bishops. However, G. Grabbe does not have strong arguments against S. Troitskiy’s assertions that a united Church center abroad does not conform to the letter or spirit of Ukase №362.

In 1935 the Council of Bishops attempted to overcome the divisions in the church by creating metropolitan districts. In accord with the Provisional Regulations of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad of 1936, four metropolitan districts were formed consisting of several dioceses. The districts chose their Metropolitan and submitted candidates for episcopal consecration for approval to the Synod. Thus the districts were only partially autonomous and were subordinate to the Karlovci Synod. (Drawing 8) Thus, the Provisional Regulations were a compromise that preserved both centralization and partial autonomy for the districts. Among the creators of this Regulation were Prof. S. Troitskiy and G. Grabbe.

The 1936 Provisional Regulations very closely followed the canonical formulation of the metropolitan districts that was worked out at the 1918 Local Council. The only difference was that in the 1936 Regulations the metropolitan districts were subordinate to the ROCA Synod, while the metropolitan districts approved by the Local Council were subordinate to the Supreme Russian Church authority.

As a result, it is quite obvious that the ROCA Synod was not a single metropolitan district in accordance with Ukase №362, but rather an alternative form of a supreme ecclesiastical authority. However, Ukase №362 says nothing about creating a church center to which several church districts would be subordinated. The Ukase did not foresee or prescribe such a development.

Our Situation

It is completely obvious that today we cannot even imagine a unified administrative center of the Russian Orthodox Church, and equally, its existence would likely not be useful. Church life, both in Russia and abroad, should be established on the basis of Ukase №362, our foundational, governing canonical document. In keeping with this Ukase, church districts should be formed, on a voluntary basis, consisting of several dioceses.

The bishops of the districts will have to elect from among their own, a First Hierarch, in regard to whom they will perform the duties enumerated in the 34th Apostolic Canon. These districts will maintain Eucharistic communion and close ties, expressed in fraternal dialogue and mutual assistance. General councils of these districts will be periodically convened to resolve issues of church-wide importance. However, in regard to administrative matters, each district will be independent. It is easy to see that a Church organized in this manner will be a return to early Christian canonical forms.

History has already resulted in the formation of churches, similar to church districts, i.e. the so-called “fragments.” Of course, these church formations have considerable defects, for example, the fact that they geographically exist one on top of the other. The problem of the “fragments” is not that they are divided, as this division has positive aspects and is quite canonical. This is how the Church appeared in ancient times and a similar fragmentation was foreseen in Ukase №362. The main problem of the “fragments” is that they do not share liturgical communion and many of them do not maintain conciliarity.

The foundation of liturgical communion between the “fragments,” as it was in the early Church, should be based on the confession of Orthodoxy and the legitimacy of the hierarchy. Eucharistic communion is not possible only with non-Orthodox, with those no correctly ordained, or with banned clergymen. If no such obstacles exist, then there is no reason to not hold joint church services. It is necessary for all of us to recognize the abnormality of a situation in which Orthodox bishops have no Eucharistic communion with each other and do not seem to concern themselves with establishing such communion.

The process of unifying the “fragments” should not be seen as an administrative merging into a single structure or as the subordination of all to one center, but rather as the establishment of Eucharistic and fraternal communion in place of today’s competition, pretensions and mutual excommunications.

The “fragments” challenge each other’s canonical succession from the pre-schism Church Abroad, however, this succession does not really exist in the form that they claim. As discussed above, the ROCA Synod was not based on any canonical acts but rather in spite of them. The rationale for the existence of the Synod was that it was the bearer of Church truth. When the Synod subsequently fell into the temptation of Sergianism, it lost this rationale. The canonical justification of the Synod was in its high spiritual and moral authority and its usefulness to the Church.

Thus a strange picture emerges: the “fragments” are competing for the possession of a non-existent legacy. The inheritance of the Church Abroad is not to be found in any particular canonical rights, as such canonical rights do not exist, but rather in the spirit of true church life, in the wisdom of the Royal Path, in connecting a firm witness in truth to preserving the tradition of the Church, all done without the extremes of fanaticism and sectarian thinking. Unfortunately, our “fragments” concern themselves too little with the attainment of this spiritual inheritance of the Church Abroad.

It is particularly strange when some small “fragment,” possessing not the slightest moral authority, claims for itself supreme power over the entire Russian Church, on the basis of some indistinct succession from the former ROCA, as, for example, was recently stated in the “Declaration of the ROCA Council of Bishops.”

The “fragments” have nothing to divide and nothing to compete over. All of them are provisional, self-governing parts of the Russian Local Church, irrespective if they are in Russia or abroad, and no matter what acronym they claim for themselves. However, they must be organized on the principle of conciliarity, in accordance with Ukase №362, so that the “fragments” can become canonical Church Districts.

Prohibitions

We will separately consider the question of prohibitions from conducting church services that have been imposed on some of the “fragments.” The episcopacy of most of the “fragments” has undeniable apostolic succession but their canonicity remains in question because when the “fragments” were formed they were judged to be schisms and their bishops were subjected to the prohibition from ministry.

With regard to the “fragments” that had been prohibited by the ROCA Synod (such as the Suzdal Synod), the problem is that the church authority that imposed the prohibitions no longer exists (i.e. it has fallen to Sergianism), and thus there is no opportunity for reconciliation and for the removal of the bans. A ban may be withdrawn only by the Church that imposed it (Apostolic Canon 32; 5th Canon of 1st Ecumenical Council).

Since there are no canonical means to lift the prohibitions imposed by the pre-2007 ROCOR Synod or by the Synod of Metropolitan Vitaliy (2001-2007), it no longer makes sense to recognize these prohibitions and they should be considered as no longer extant. These bans could be removed by a general council of bishops of the “fragments.”

As for mutual prohibitions imposed by the hierarchs of the “fragments” on each other, these prohibitions were often imposed on the basis of incorrect canonical considerations. For this reason, they can be simply ignored.

In the words of one modern church personality, “the process of ‘gathering the fragments’ should in its first stage be more ‘ideological’ rather than organizational and administrative. It is time to finally formulate a rich and compelling ideology, or to use theological language, an ‘ecclesiology of the fragments,’ which will gradually become more popular and influential than the old ‘administrative-Synodal ecclesiology’.”

In my opinion, this “ecclesiology of the fragments” is clearly enough defined by Ukase №362. As Archpriest Nikolay Artemov expressed it: “In essence Ukase №362 provides sanction for the reorganization of the whole Russian Church on the principle of metropolitan or church districts that preserve spiritual unity among themselves until the opportunity arises to freely determine their common life at the level of the entire Russian Church.”

I will conclude by citing the words of one of the confessors of the Russian Church: “History shows us that at some periods of time nothing united the parts of the Universal Church except Communion from the One Bread of Christ, who rules in heaven … the Church does not die when its external unity collapses. It does not value external organization, it is concerned with preserving its truth.

Amen.

Bishop Andrei (Erastov)

Illustrations:

1.The Local Council of 1917-1918

2. Met. Antony (Khrapovitskiy)

3. Professor S.V. Troitskiy

4. Bishop Gregory (Grabbe)

5. Bishops’ Council ROCA 1981